South Australia - Sport

- Archery

- Athletics and Gymnastics

- Baseball

- Basketball

- Billiards

- Bowling

- Boxing and Wrestling

- Coursing

Cricket

- The Adelaide Oval

- Miscellany

- Croquet

- Cycling

- Fishing

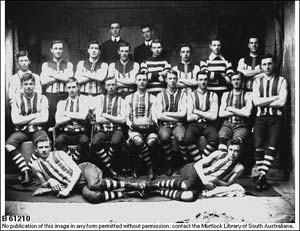

- Football

- Fox Hunting

- Golf

- Greyhound Racing

- Hockey

- Horse Racing

- Lacrosse

- Miscellany

- Pigeon Racing and Shooting

- Polo

- Quoits

- Rifle Shooting

- Roller and Ice Skating

- Rowing

- Shinty

- Soccer

Swimming and Bathing

- City and Public Baths

- Miscellany

- Tennis

-

Vigoro

- Yachting

Sport and Recreation in South Australia

(Taken from Geoffrey H. Manning's A Colonial Experience)

-

No branch of sport can be made either better or more popular by a mistaken effort on the part of its principal supporters to serve it at the expense of any other acceptable recreation. Sport should be the business of sportsmen.

(Register, 29 August 1923, p. 8.)

The colony of South Australia was planned as 'a new Britannia in the antipodes' by Edward Gibbon Wakefield and other theorists. This edict envisaged it becoming an 'entire British community' with the rigid class structure of the 'Mother' country and, to this end, the colonial gentry strove to adopt a lifestyle similar to which they had aspired in England. This trait was exemplified, for example, in Adelaide and infant villages such as Kensington and Beaumont where they built gracious villas, formed literary and scientific associations and became members of the exclusive Adelaide Club.

By 1846 Francis Dutton was to proclaim that 'all the purely English sports are kept up . . . and are . . . much patronised'. To achieve this end the 'superior class' among the colonists imported horses from India for polo and from Arabia, or England, for horse racing and hunting, at which the wild dog and kangaroo replaced the fox and deer. Later, they cruised the placid waters of St Vincent Gulf and went cycling when it was considered to be the 'proper' thing to do, all of which could be considered to be, more or less, affirmations of status.

In time, other elite sports such as rowing, yachting and archery came to the fore, while the noble game of golf became fashionable at the end of the 1860s. When tennis became popular at the close of the 1870s, the gentry adopted the game and the gracious homes of Adelaide became the venue for a 'linking' of the sexes at garden parties, where the term 'lawn tennis clique' described those aspiring to be numbered among the upper echelons of colonial society. Thus, sports were looked upon as 'symbolic displays of status' at which members of the new gentry derived confidence from the activities of others of a similar ilk doing similar grand things.

The relatively impecunious workers had less time and money to engage in sporting activities. They displayed a complete indifference to the activities of the gentry and resorted to games on a lower rung of the social scale. Some publicans made the most of the opportunities available by providing venues and promoting games such as cricket, football, boxing, wrestling and skittles in close proximity to, or within the confines of, their places of business. It was here that labourers were found playing cricket on the worn footways beside the public houses and having side wagers on the result.

By the close of the 1850s organised sport was, essentially, in the hands of the 'superior classes' or 'leading colonists' striving consciously to emulate English provincial gentry. They engaged in horse racing, hunting to the hounds, shooting pigeons for £20 a side and gambling heavily, while condemning perceived inferiors for their participation in such brutal amusements as boxing and wrestling.

A stroll around Adelaide at this time would have revealed splendid houses of worship, elegant public buildings and grand commercial establishments reflecting great credit on the spirit, enterprise and energy of the inhabitants. But, amidst all this was an absence of anything like innocent amusement and recreation. Indeed, it appeared that prosperous circumstances and liberal salaries, without ample means of rational entertainment, tended to demoralise the colony rather than improve it.

At this time the prevailing idea of a summum bonum seemed to be intoxication, in proof of which was the extraordinary number of public houses, without any other claim to patronage other than the vending of strong drink, supported by such a thin population. With the exception of the Hotel Europe there was no place where a person might enjoy the comfort of a quiet glass and charms of good music.

As to the mere worldly aspect of the question, there was little doubt in the minds of many reasonable citizens that a fair expenditure of government resources, for the purpose of procuring rational and harmless amusements for the people, would have been a highly reproductive investment of public funds, and a means of enticing many youths to cease the immoderate use of strong drink and frequenting dancing saloons of questionable repute. With the advent of the Saturday half-holiday in 1865 the working man acquired the leisure time necessary to play games on a regular basis, while the closing of many shops and other places of business on Wednesday afternoons was achieved by direct representations from the working class, with a view to securing practice time for club sport.

The employers of labour, who consented to these new working conditions, deserved the thanks of the community at large. It was easy to point out the advantage of holidays and recreation in promoting the morality of society, for there is an instinct within that refuses to be satisfied with ordinary occupations and yearns after amusement as a necessity of being. It is not confined to childhood, with its frisking life and joyous gambol; it runs through every age and condition, save where it has been smothered to death by the selfishness of business or the austerities of religion.

Confine a daughter to the house, with its ceaseless round of necessary but frivolous duties, and no picnic parties or pleasant walks to break the monotony of life, and you have not only sullied its charms, you have given a wrong bias to its action. Keep a son hard at work at his chosen calling from Monday morning to Saturday night, and not an hour from week's end to week's end for joyous recreation, and you have violated one of the requirements of parental conduct. He must have amusement.

Deprive him of healthy and invigorating sports and he will seek his enjoyment in the haunts of vice. Indeed, there can be no doubt that the wide-spread profligacy, that had eaten deep into the heart of most of the great cities of the world at that time in our history, would have been largely restrained if more recreation had been given to the over-worked.

By the general adoption of the eight-hours system in the mid-1870s, and the increased rate of wages consequent upon the demand for all kinds of labour, the position of a large number of working men and their families improved materially. However, the mere possession of additional leisure and increased income was of little value unless both were turned to good account.

Some had a taste for reading and a desire for self-improvement, while others were glad to improve the condition of their homes and promote the welfare of their families and, as such, the opportunity of gratifying their inclination was invaluable. Many were connected with various religious organisations and found in them useful employment of service to the community.

But, after making all due allowance, there remained a large class without these resources and to whom the improved condition of the labour market brought no corresponding advantage. Unoccupied time was apt to hang very heavily. Workmen's homes were not always rendered as attractive as they might have been and sometimes the head of the family was almost compelled to seek comfort elsewhere, while unmarried men, of course, had to go abroad for recreation. Under these circumstances it was no great wonder that amusement was sought in a way neither salutary nor profitable.

There were entertainments in considerable variety as I have narrated elsewhere, but they were often unsuitable and costly. The Institute in Adelaide was out of the way and its accommodation strictly limited, so it was natural for the most convenient place of resort to be the most frequented. This situation was remedied in suitable suburban locations by the provision of well-lighted and well-ventilated rooms, where a supply of periodicals was kept, a smoking room provided, provision made for those who chose to indulge in a quiet game of draughts or chess, and the important matters of cleanliness and warmth duly attended to. Religious people, however, did not always perceive clearly the importance of employing auxiliary measures to assist them in their undertakings. Indeed, much good could have been done other than by sermons, in places other than churches, and at times other than on Sundays.

As for temperance bodies their motives were, no doubt, well-meaning, but whether their methods were as wisely directed as might have been was open to considerable question. The complaint was made that after so many years of toil, the vice of intemperance was not checked sensibly and the blame laid on the number and attractiveness of public houses. If these pious souls had attempted to outbid the hotels, by providing a greater attraction at a lower cost, they would have ensured public patronage and support, and if they had provided suitable resorts for the working man on the principles of temperance, with materials for social enjoyment and mental improvement, would have gained a larger amount of credit than what was achieved by wordy agitation.

In 1880 a newspaper correspondent mirrored my views:

-

It is strange that the Nockites of the Lower House, none of whom are satisfied with the simple fare that sufficed for John the Baptist, or see fit to shun entirely, however they may anathematise the sparkling cup or the flowing bowl, have not a more kindly feeling towards the poor man whom they endeavour to rob of his Sunday beer, or the poor publican whom they love to persecute. It is, however, so much easier for great moralists to preach than to practise rigid abstemiousness.

Archery

General Notes

An archery club meeting is reported in the Register,

2 February 1857, page 2h and

an "Annual Ball" on

16 October 1858, page 3c; also see

14 May 1860, page 2h,

4 June 1860, page 3e,

15 June 1863, page 2f,

16 November 1863, page 2h.

"The Archery Ball" is reported in the Chronicle,

27 October 1860, page 6g.

A sketch of a meeting of the Adelaide Archery Club is in the Australasian Sketcher,

8 July 1876, page 61.

A meeting of a reconstituted archery club is reported in the Observer,

18 September 1875, page 7a; also see

Chronicle,

23 October 1875, page 16e.

The formation of the Adelaide Archery Club is reported in the Register,

12 August 1876, page 5a; also see

30 October 1876, page 5c,

27 November 1876, page 5b,

15 January 1877, page 7b,

9 April 1877, page 5e,

7 May 1877, page 5c,

8 April 1878, page 5a,

20 May 1878, page 5d,

25 August 1879, page 4f,

18 May 1880, page 5b.

An Adelaide Archery Club Ball is reported in the Observer,

29 September 1883, page 6c.

Also see Observer,

6 October 1883, page 19c,

17 November 1883, page 19a,

Register,

6 November 1883, page 5b,

29 April 1884, page 5d,

6 November 1884, page 3h,

2 November 1885, page 5g,

18 May 1886, page 6g,

Express,

20 October 1886, page 3g,

Observer,

26 November 1887, page 20a,

15 August 1888, page 5c,

Express,

7 June 1889, page 4c.

Advertiser

10 December 1937, page 10d.